As the old saying goes, there is nothing new under the sun. We like to think of voter fraud and accusations of stolen elections as modern grievances, but in truth, America has a long and sometimes bizarre history with such claims. Back in the late 1860s, as the dust of the Civil War was still settling, Democrats in the former Confederate states found themselves largely cut out of the political process. In places where the Republican Party had once been little more than a Northern curiosity, its candidates were now being elected to high office across the South.

While researching the postwar activities of my great-great-grandfather, Colonel DJ Dobbs—a former enrolling officer for the Georgia state militia for Cobb County—I stumbled upon an article in the *Atlanta Weekly Intelligencer*. The piece claimed that Radical Republicans had managed to take the U.S. Senate seats in Florida through vote tampering. Interestingly, this allegation didn’t come from a Southern newspaper but rather from a Democratic-leaning publication up in Pennsylvania.

The article told the story of a Florida man, a carpenter in that state, who was hired to construct a very special ballot box for a special election.

The 1868 presidential election was the first of the Reconstruction era, marking a new and uncertain chapter in American history. Ulysses S. Grant, leading the Republican ticket, squared off against Horatio Seymour of the Democratic Party in a contest that would set the tone for the nation’s future. For my great-great-grandfather, who had managed to rehabilitate his standing, it was a personal milestone as well—he was back in the fold, serving as a delegate to the Georgia State Democratic Party convention.

It was the first election to take place after slavery had been abolished, and, perhaps most notably, the first in which African American men could vote in the reconstructed Southern states under the First Reconstruction Act. The political landscape was shifting in ways no one could have imagined just a few years prior, and with that shift came controversy, power struggles, and, of course, accusations of fraud—echoes of which still linger in our politics today.

During this time, things were still fairly volatile in the South. Three of the former Confederate states (Texas, Mississippi, and Virginia) were not yet restored to the Union, their electors could not vote in the election. The 1868 vice-presidential candidate for the Democrats, Frances Blair Jr, a Missouri politician, was a rabid racist who, in his national speaking tour, was warning of the rule of “a semi-barbarous race of blacks who are worshipers of fetishes and polygamists” and who wanted to “subject the white women to their unbridled lust.” As part of their campaign, Republicans advised Americans not to vote for Seymour, as there was a danger that Frank Blair might succeed him. Also, in some states, Frank Blair’s own party considered him a liability and wanted the VP candidate to restrict his campaigning to Missouri and Illinois.

Former Union Army Gen. Ulysses S Grant won the popular vote with only a slim majority, and this shocked the political elite of the Republican party. Along the border, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware went overwhelmingly Democratic. Kentucky’s case was influenced by hostility toward the Radical Reconstructionists, which had led to the state’s first postwar government being almost entirely composed of former Confederates. There were accusations that the Democrats had cheated in New York state. Georgia’s vote was contested at the electoral count, with the Republicans claiming the Democrats won only by “violence, fraud, and intimidation, and Georgia’s vote in Electoral College likely would have been disallowed if the Democratic victory had been decisive.”

The Union Army had recently pulled out of Georgia, and the vacuum that was created allowed the Redeemers to begin the process of reasserting political control over the state. The Redeemers or Redemptionists were generally led by the rich former planters, businessmen, and professionals, and they dominated Southern politics in most areas from the 1870s to 1910. In the Gilded Age, they were known as Bourbon Democrats.

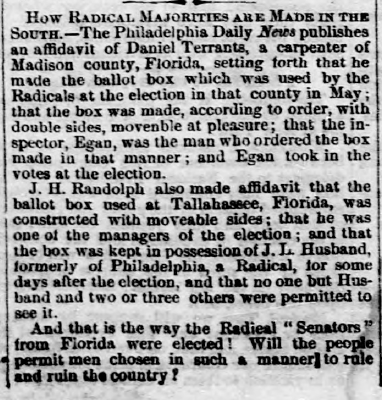

In the July 15th edition of the Atlanta Weekly Intelligencer, an item appeared entitled “How Radical Majorities Are Made in the South.” It states that the Philadelphia Daily News published an affidavit by a Florida carpenter hired by the Republican Party to build a ballot box with “double sides, movable at pleasure.” It further states that this ballot box with movable sides was used in Tallahassee, Florida. It proclaims that “this is the way that radical Senators were elected” in 1867. The article closes by asking: “Will the people permit men chosen in such a manner to rule and ruin the country?”

Unfortunately, the article does not describe how the box was operated to facilitate the fraud effort.

A few weeks later, in the Wednesday, July 29, 1868 edition of the Weekly Intelligencer, they announced that the Democratic Party state convention was called to order and was followed by a roll call. Listed as a delegate representing the County of Cobb was my great-great-grandfather.

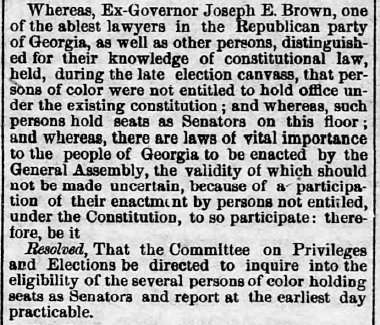

Following this, the convention nominated several men as candidates for each of the congressional districts in the state of Georgia. In that same edition of the paper, there was a curious item that was saying the quiet parts out loud.

The Civil War-era Gov. of Georgia was a former Whig named Joseph E Brown and the fact that he was a former leader of the Confederacy did not seem to matter now that he was a member of the Republican Party of Georgia. Also early settlers of Cobb County, Gov. Brown and his wife were close friends of the Dobbs family.

The item in the paper indicates that the Democratic Party and the Republican Party in Georgia might have disagreed on some things. However, one thing they could all agree upon was that the Georgia state constitution forbade persons of color from holding office. Now that the federal government had released its hold on the state of Georgia, the original intent of the white politicians of both parties was to restore the status quo to what it had been in the antebellum days.

This was the dawn of Jim Crow, and these attempts to disenfranchise the newly freed slaves set in motion acts of violence and terrorism against Blacks and would result in the resumption of military rule throughout the state less than a year after the Union Army had gone home.