Why the Gaume family and other collateral families left northeastern France to settle in northeast Ohio is not entirely clear. The economic and political climate in post-Napoleonic France in the 1830s has been described as humdrum. Following the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the Bourbon monarchy was restored, and Charles X became king in 1824. He tried to restore the throne to its former level of absolutism but was overthrown in the July Revolution of 1830. The revolutionists placed Louis-Phillipe of the Orleans branch of the Bourbons on the throne. Many Bonapartists and Republicans who longed for the glory days of the Napoleonic Empire were not happy with this arrangement. Still, as France was at peace and prosperous during this time, it was accepted. The poorer classes of France became dissatisfied because only the wealthy could vote or hold public office. However, this situation did not boil over to an open revolt until nearly twenty years had gone by when the whole of Western Europe became embroiled in the Revolt of 1848.

It appears that most of the Gaume families who came to Ohio and settled in Stark County left France in the early 1830s. A significant factor in drawing these people away from Europe and into Ohio was building the canals that opened up access from the east to the Ohio valley. The land was cheap then, and the idea that a poor peasant from France could own his farm had an immense appeal to it.

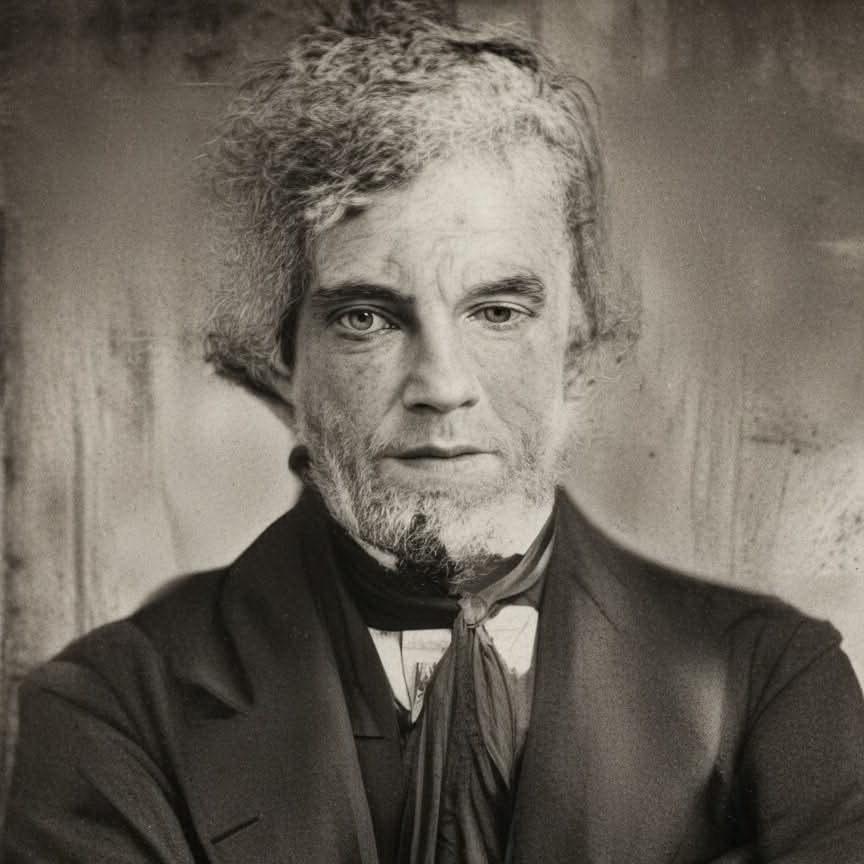

Francis Gaume,Sr. (Jean Baptiste Francois Xavier Jeanin-Gaume)emigrated alone at 25 and landed in New York on April 25, 1833, on board theSS Charles Carroll out of Havre, France. His occupation is listed as blacksmith. The Atlantic crossing in the 1830s was likely to last anywhere from fourteen to twenty-eight days.

Patrick Drouhard, an Ohio historian, provided me with some details regarding the emigration route probably taken by his ancestors from St. Sauveur, France, to Massillon, Ohio, in 1833:

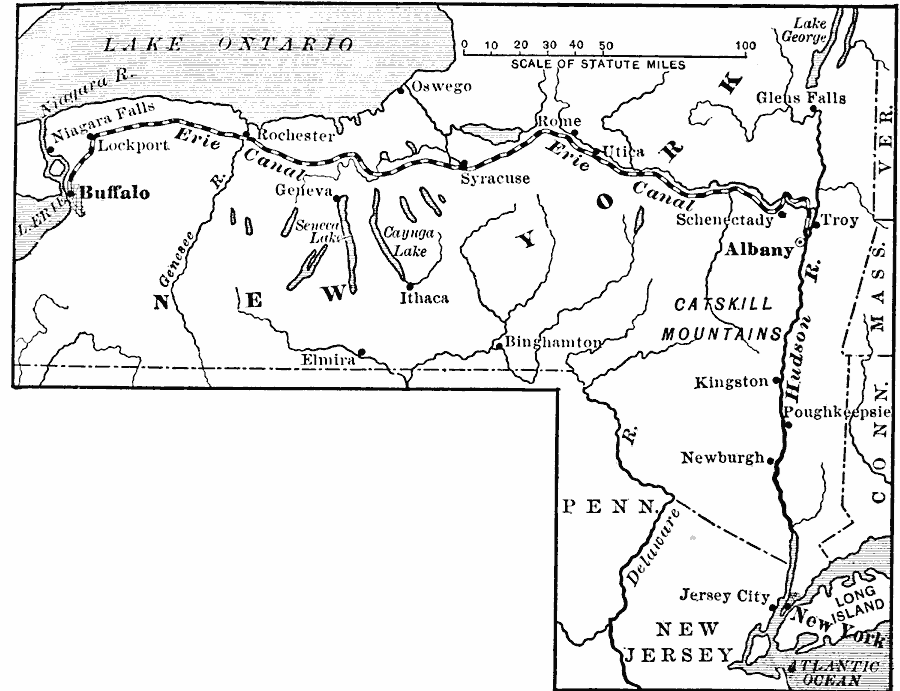

Pierre and Marguerite Drouhard came from St. Sauveur, Department of Haute Saone, France in 1833. They sailed from Le Harve, an Atlantic port on the French coast, to New York City and north-central Ohio. Here is their approximate travel route. They traveled overland from St. Sauveur to Vesoul, then from Port-s-Saone at the Saone River. They traveled southwest and then west, a distance of approximately 36 miles. At Port-s-Saone, they boarded a boat or barge and followed the Saone River southwest to St. Jean-de Losne – a distance of 50 miles. At St. Jean – de Losne, they entered the Canal de Bourgogne and traveled northwest through Dijon, Montbard, Ancy–le-Franc, and finally to Migennes, where they picked up the Yonne River, which flows into the Seine River (150 miles). They continued on the Seine River in a northwest direction to Paris and finally the Atlantic port city of Le Harve (a distance of 110 miles). They traveled approximately 400 miles from their home to Le Harve. It took them around four weeks. From Le Harve, they sailed across the Atlantic to New York City and then north up the Hudson River to Albany, New York. They entered the Erie Canal at Albany, which took them through Syracuse, Rochester, and finally Buffalo, New York, a distance of 360 miles. From Buffalo, they took a Lake Erie boat to Cleveland (approximately 100 miles). At Cleveland, they entered the Cuyahoga River and then the Ohio Canal, which ran south through Akron, Canton, and Massillon to Bolivar, Ohio (a distance of about 60 miles). At Bolivar, they left the Canal and traveled overland approximately 20 miles to Mt. Eaton, Ohio, where they settled. The nearly four thousand-mile journeys probably took about 12 weeks to complete.

Out of all the possible modes of transportation that my ancestors might have used during their migrations, I find traveling by way of canals fascinating and exotic. From some first-hand (tour book) accounts of travel on the Erie canal, most written in the 1830s – The Great Water Highway through New York State (1829), Three Years In North America (1833), and Some Account of a Trip to the “Falls of Niagara” (1836) – I have reconstructed what Francis Gaume’s trek to Ohio from New York must have been like for a young immigrant.

Steamboats traveling from New York could convey several hundred passengers on the 164-mile trip upriver to Albany. Both day and night boats made the 10 ½ to 16-hour trip. The duration of the journey depended on how many stops the steamboat made along the way. The fare for the “first-class” travelers was $2 to $3, with meals being extra. Before steamships, the trip upriver might have taken eight days.

The Erie Canal begins at Waterford (a few miles north of Albany) and courses 363 miles to Buffalo on Lake Erie. Construction of the Canal started in 1817 and was completed in 1825. The original channel had 83 locks and 18 aqueducts. It was 40 feet wide and 4 feet deep. By way of a series of locks on the Canal, the boats would gradually reach Buffalo at 560 feet above the Hudson River valley.

Most passengers would not get on the Canal at Albany but instead take a 9-passenger stage ride to Schenectady and begin their canal journey there. According to contemporary accounts, there were too many locks on the 28-mile portion of the Canal from Albany to Schenectady. Traveling by Canal would add another 24 hours to the trip, whereas the 17-mile trip by stagecoach was much shorter and quicker. With a combination of a horse-drawn and steam-pulled stage, the journey to Schenectady took only an hour and a half and cost 62 ½ cents in 1836.

Passengers usually traveled in the faster canal packet boats, whereas freight was moved in line boats. The packet boats were pulled by three horses and traveled about four mph. By contrast, the line boats used two horses and cruised about three mph. Passengers were each charged 3 to 4 cents per mile. The Canal was owned and operated by the state of New York. Yet, private companies provided services on the Canal that competed with one another for passengers and freight.

At Schenectady, passengers arriving from Albany were accosted by “runners” who represented the different packet boat companies, each vying to fill their boat with passengers for the 80-mile trip upriver to Utica. Depending on delays caused by problems with the locks along the way, the journey to Utica could take over 24 hours. Along the way – usually at the locks – there were “hotels” that sold fruit and liquor. Passengers would jump off the packet boat, make their purchase, and then jump back on the boat.

Low bridges were hazards along the Canal, and passengers were cautioned to pay attention to the stewards would frequently yell out “Low Bridge!” meaning for everyone to duck down as the boat passed under a bridge. During the 1832 presidential election, the democratically-inclined stewards might yell out something like “All Jackson men bow down!” hoping that the aristocratic Adam’s supporters might get conked on the head by a passing bridge.

Passengers arriving at Utica would switch to another packet boat to take them on to Rochester, sometimes just walking over the side of one boat and onto another. The 160-mile trip from Utica to Rochester would take about 26 hours and cost $6.50 in 1836.

Twenty-two miles upriver from Utica is Little Falls. A series of falls or rapids made several locks necessary at that location. Beyond that, the Canal enters a relatively straight and flat region called the German Flats.

At Rochester, passengers would switch again to another packet boat to take them the remaining 93 miles to Buffalo and another 26-hour trip. Beyond Rochester, at the town of Lockport, a series of five double-locks elevated the boats another 60 feet. Double locks allowed for traffic going both ways to pass through the locks simultaneously. Near Buffalo, the packet boats would enter Tonawanda creek for the remaining 12 miles of the journey.

From Buffalo, passengers could board steamships on Lake Erie bound for the west. In addition, as the emigrants headed west, many a sightseer made the trip up the Canal in the 1830s to visit Niagara Falls. Many travelers from Great Britain used the Erie Canal to get to Canada. They found the Erie Canal a much better route than going up the St Lawrence River through Montreal. Since the port at Buffalo was closed for five months in the winter, most people would have made the journey in the spring and summer months.

After arriving in Ohio, Francis Gaume (Sr.) became a farmer. The Gaume farm was located south of the village of Louisville near where Miday Road splits from the present Route 44. Later after Francis Gaume died, the farm became his wife’s property. In 1875 the farm and the land around it, in the south part of Nimishillen Township, was described as follows:

Eighty acres just south of the Miday Road- Rte. 44 split was owned by a Mrs. Gaum. Seventy-four acres immediately south of that was owned by P. Rebellot (sp). Mrs. Gaum’s land was abutted to the north by land owned by L. Chevraux; to the east by land owned by C. Saunier. The 157-1/2 acres to the west are not identified by the owner. The land immediately to the west of P. Rebellot belongs to V. Balm; to the east, C. Saunier; to the south was the settlement of Belfour (sp). P. Scholley owned 81 acres of land just east of Louisville at that time and 120 acres in the southeast corner of Nimishillen Township.

This story and others can be read in my book Gathering More Leaves – Vol. I, available for Kindle from Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing.