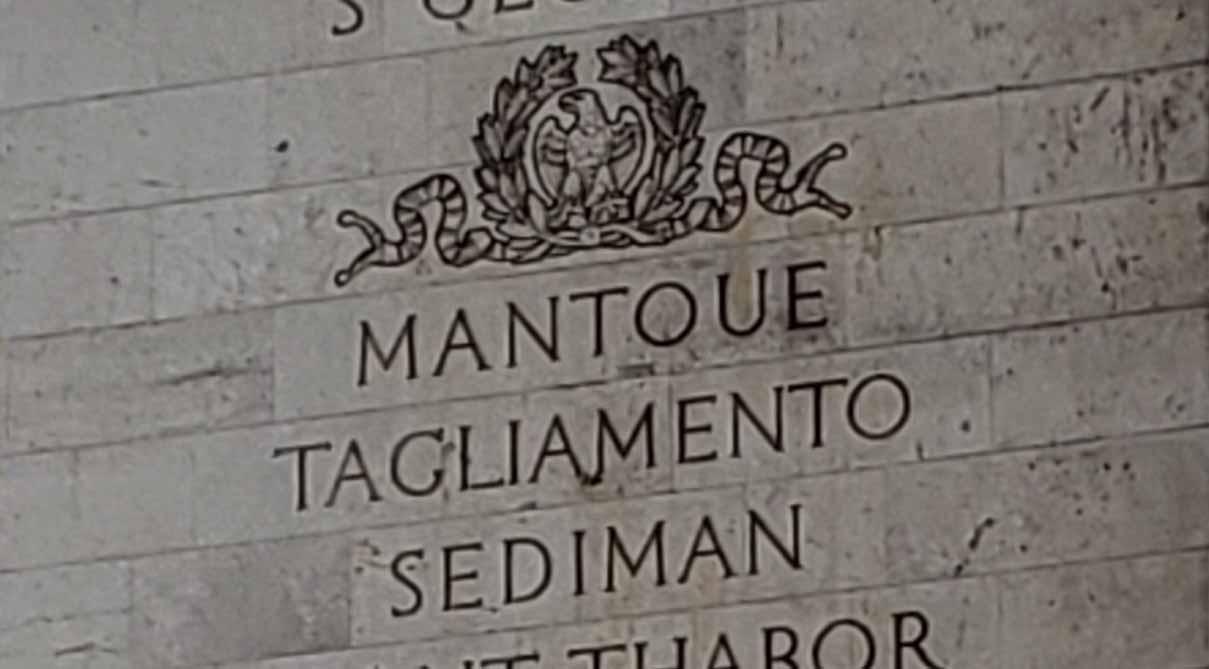

In 2023, during my visit to Paris, my final stop before heading home was the Arc de Triomphe, located just a few blocks from our hotel. The Arc de Triomphe is one of Paris’s most iconic landmarks, standing at the western end of the Champs-Élysées at the center of Place Charles de Gaulle. Commissioned by Napoleon in 1806 after his victory at the Battle of Austerlitz, the monument honors those who fought and died for France during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

I took several photos of the beautiful columns that support the archway, but the column that held the most significance for me was the one inscribed with the name of a battle where one of my ancestors, according to my research, had fought. This battle, “Le Var,” marked a crucial moment in my ancestor’s military service. It bugged me that of 158 names of battles – every one a victory of the French Army – only two, Le Var and one other, are missing a Wikipedia article.

The Battle at Le Var (technically a series of clashes) was named after the river that flows in southeastern France through Nice into the Mediterranean. As I later learned, this was a significant victory for the French as they prevented the Austrians from invading France and threatening Nice.

After returning home, I thought there must be more to this story. I made a mental note that I should go back and review what I could learn further about my ancestor’s military service during the last decade of the 18th Century. So, this past summer, I did that, and sure enough, I learned that I had missed out on many details about the unit that Lucien François Gaume served in.

I learned that three more battles were inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe, where he was present. In addition, I discovered that he crossed the Alps with the French Army three years before Napoleon made his famous Crossing of the Alps.

The following is a revision of the Luke François Gaume section in the chapter entitled “My French Connection” in my book Gathering Leaves. Allow me to start by explaining how I came to learn that my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather was a veteran of Napoleon’s army.

More than ten years ago, I learned that in 1857, my 4th great-grandfather, Lucien François Jennin-Gaume, was awarded a campaign medal by Emperor Napoleon III. This medal, the Médaille de Sainte-Hélène, was given to surviving French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars veterans from 1792 to 1815. Established by decree in 1857, the medal recognized veterans who had served in campaigns under Napoleon I. Lucien received his medal at 83.

The information I initially uncovered came from a French-language source, which has since been translated into English and relocated to a new site: https://www.stehelene.org/. The database provided basic details that helped me identify Lucien: his hometown, rank, and the unit he served with. My Gaume family came from a small village in the foothills of the Jura Mountains, less than 10 kilometers from the Swiss border. The database listed Lucien François Gaume from Montécheroux as a soldier in the 20th Demi-brigade, a Light Infantry unit active during the Revolutionary Wars from 1792 to 1803.

At the time of my initial research, I needed help finding information about the structure of the French army during the reign of Napoleon I. My essential resource was Digby Smith’s “Napoleon’s Regiments: Battle Histories of The Regiments of The French Army 1792–1815,” a comprehensive guide to French army units of that era. Fortunately, the database listed Lucien’s unit as “20e DbdLé,” shorthand for “20e Demi-Brigade Infanterie Légère.” I realize now that I failed to follow up on some essential items while researching. For example, asking and answering, “What is the difference between ‘line infantry’ and ‘light Infantry’?”

Digby George Smith (1935–2024), who also used the pseudonym Otto von Pivka, was a British military historian and an authority on the Napoleonic Wars. His Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book: Actions and Losses in Personnel, Colours, Standards, and Artillery, 1792–1815 (1998), is considered a standard for French Revolutionary War and Napoleonic War historians, re-enactors, and hobbyists.

Smith’s book on Napoleon’s Regiments is divided into sections by unit type: Imperial Guard, Line Infantry, Light Infantry, Colonial Troops, and more. Each unit is listed under the names they held at the start of the Napoleonic era, after 1803. I initially assumed that the 20e DbdLé referred to the “20e Régiment d’Infanterie Légère.” Fortunately, I was partly correct, as there wasn’t a one-to-one correspondence between the old demi-brigades and the new regiments. After becoming Emperor, Napoleon reorganized the army and restored the use of the word “regiment,” a term that had been replaced by “demi-brigade” during the Revolution due to its royalist connotations. Similarly, “colonel” was replaced with “chef du brigade.”

The 20th Demi-brigade was disbanded in 1803 and was amalgamated into the 7th Light Infantry Regiment (7e RILé). The number 20 remained vacant throughout the Napoleonic Empire. Napoleon’s restructuring increased the number of Light Infantry regiments from 20 to 37.

Yet, Lucien was discharged from the army in 1802, which allowed him to marry my 4th great-grandmother, Marie Therese Pequignot, on December 27, 1802. At the time, Marie was 20 years old, and Lucien was 28. Here is a significant clue as to when Lucien entered the military because he married several months before the War of the Second Coalition ended and the disbanding of his unit. This boosts my theory that he entered the military in 1792, immediately following the declaration of war against Austria in April. In their first action against the Austrians, the French armies were victorious over the Prince-Bishopric of Basel at Porentrui. The town of Porrentruy, where the Prince-Bishop had his last castle, is about 30 kilometers east of Lucien’s hometown of Montecheróux. Like many patriotic men, he probably signed up for ten years, believing the war(s) would be over long before. Little did he know that for the next 23 years, almost nonstop fighting would engulf Europe and the entire world.

The Sainte Helene’s medal, created in 1857 by Napoleon III, rewarded the 390,000 soldiers still living at the time who had fought with Napoleon I during the 1792-1815 wars. The decorated soldiers were born around 1765-1797 and still lived in 1857. All of them belonged to the French army between 1792 and 1815. In total, 405,000 soldiers were decorated between 1857 and 1870, and 350,000 French and 55,000 foreign soldiers were decorated.

Luc Francois was born in 1774 in Mambouhans, Doubs, and passed away on March 3, 1860, in Montecheroux, Doubs, France. At 18, he witnessed France declaring war on Austria in 1792. By 1794, during the Reign of Terror, he was 20. In 1796, Napoleon’s 1st Italian Campaign unfolded two years later when Luc was 22. In 1800, as Napoleon embarked on his 2nd Italian Campaign, Luc was 26. The peace treaty of Amiens between Britain and France was signed in 1802, the same year Luc, then 28, married Marie Therese Pequignot. Their first child was born in 1803.

Napoleon’s machine acquired every able-bodied and un-married man who were citizens of France and surrounding nations under French control, including Belgium and parts of Germany and Switzerland. When exactly he joined the service is still a question. As I mentioned above, my theory is that he joined as a volunteer along with hundreds of thousands of others following the issuance of La Patrie en danger (the Law Of The Nation In Danger) in July 1792. Otherwise, given his age, he would have surely been conscripted following the Levee en Masse in August 1793.

At this point, it remains unclear what military unit he would have been in before the creation of the 20th Demi-brigade (20e DBdeLé) in 1796 under what is known as the second amalgamation of the French army.

Three Possible Origins of the 20e DBdeLé

- Chasseurs du Gevaudan 🡪 2nd Bn, 10e DBdeLe 🡪 20e DBdeLé 🡪 7e RILé (is 10e a misprint ?)

- 16e Bn, Chasseurs à Pied (or 2e du la Légion du Centre) 🡪 (combined with the 20e)

- 1erBn, Légion de la Moselle 🡪 (combined with the 20e)

According to Digby Smith, the 20th Demi Brigade originated as the Chasseurs du Gevaudan, whose name indicates a regiment that originated in a region of the ancien regime southwest of Lyon. The two other battalion-level units combined to create the 20th Demi brigade were the 16e Chasseurs à Pied and the first battalion, Légion de la Moselle.

Definition of Terms

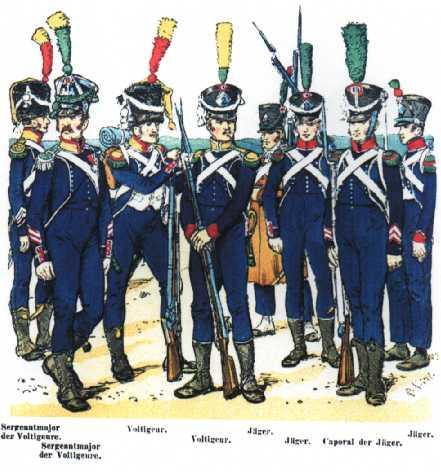

“Chasseurs à Pied” translates to “Hunters on Foot” in English. It refers to a specific type of French light infantry unit that was highly mobile and skilled in skirmishing. Unlike line infantry, who fought in more structured formations, the Chasseurs à Pied were trained to operate in loose order, move quickly, and engage in more flexible combat roles such as surveillance and flanking maneuvers.

These units played a significant role during the Napoleonic Wars and later conflicts and are known for their speed, precision, and versatility in the field. The term distinguishes them from Chasseurs à Cheval, who were light cavalry.

The Chasseurs à pied (light infantry) were initially recruited from hunters or woodsmen. The Chasseurs à Pied, as the marksmen of the French army, were considered an elite unit.

In 1793, the Ancien Régime’s Chasseur battalions were merged with volunteer battalions in new units called Light Infantry half-brigades (demi-brigades d’infanterie légère). In 1803, the half-brigades were renamed regiments.

This branch of the French Army originated during the War of the Austrian Succession when, in 1743, Jean Chrétien Fischer was authorized by the Marshal de Belle-Isle to raise a 600-strong mixed force of infantry and cavalry. It was called Chasseurs de Fischer

The chasseurs à pied were the light infantrymen of the French Imperial Army. They were armed the same as their counterparts in the regular line infantry (fusilier) battalions but were trained to excel in marksmanship and in executing maneuvers at high speed.

The light infantry soldiers were expected to march 30 miles a day. Napoleon often boasted that the Imperial Roman army could march only 25 miles a day.

In France, during the Napoleonic Wars, light infantry were called voltigeurs (riflemen) and the sharpshooters were tirailleurs.

For the light infantry, orders were sent by bugle or whistle instead of drums (since the sound of a bugle carries further and it is difficult to move fast when carrying a drum). Light infantry was considered elite since they required specialized training emphasizing self-discipline, maneuver, and initiative to carry out the roles of light infantry and those of ordinary infantry.

In the French army of Napoleon, the main difference between line infantry and light infantry was how they fought and were armed:

Light infantry fought as skirmishers, taking advantage of cover and the space between soldiers. They were armed with sabers and were often selected to lead divisions into battle. Light infantry was considered an elite unit that required specialized training in self-discipline, initiative, and maneuvering.

Meanwhile, line infantry fought in rigid lines shoulder-to-shoulder and dominated the field. They comprised grenadiers, riflemen, and skirmishers who fought on foot and used rifles. Line infantry maneuvered in columns to move quickly or to carry the attack into the enemy.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chasseur

History of the 20th Light Infnatry Demi-Brigade

(20e Demi-Brigade Infanterie de Légère)

1796

The French Wikipedia section on the subject of 20e DbdLé gave the following summary of the unit: “La 20e demi-brigade légère, fait les campagnes de l’an IV (1796) et de l’an V (1797) à l’armée de Sambre-et-Meuse, celle de l’an VI (1798) aux armées d’Allemagne, de Mayence et d’Helvétie et celles de l’an VII (1799) de l’an VIII (1800) et de l’an IX (1801) à l’armée d’Italie.”

“The 20th light demi-brigade, made the campaigns of the year IV (1796) and of the year V (1797) in the army of Sambre-et-Meuse, that of the year VI (1798) in the armies of Germany, Mainz and Helvetia and those of the year VII (1799) of the year VIII (1800) and of the year IX (1801) in the army of Italy.”

A reference to the 20th demi-brigade (20e DBdeLé) is found in “Correspondence de Napoleon I” (pub. 1853) in a letter from Napoleon to General Berthier dated 11 germinal an IV (March 31, 1796) in which he is ordering that 20e DBdeLé exchange places with the 15e DBdeLé at Nice and prepare for the invasion of Italy.

Yet, according to the Napoleonic Wars Data Book (and the French Wikipedia), the 20e DbdLé was with the army of Sambre-et-Meuse (as of June, 1796, the Armée du Rhin et la Moselle) under the command of General Jourdan (see Rhine campaign of 1796). This was from June until the end of the year.

April/May 1796 – The Second Amalgamation formed the 20eDbdLé from the units I listed earlier. This occurred in either April or May in preparation for the campaign on the Rhine that began in June 1796.

June 19, 1796 – The 20eDbdLé was possibly at a clash at UCKERATH. The Data Book notes that the order of the battle was the same as the battle of WÜRZBURG, which occurred on September 3 (the 20e DbdLé is listed on page 115).

Any place where there is a lack of details and an indication that the order of battle is the same as the previous battle where the 20e DbdLé was present, we may assume that they were there.

Uckerath is a village in ‘Bergisches Land’ hills in the western German province of Nordrhein-Westfalen, about 20 km east of Bonn on the River Rhine and route 88. Historians consider it a drawn match between the French and the Austrians.

The French forces consisted of 24,000 men versus a total of 30,000 Austrians. The French losses were 2300 killed and wounded. Seven hundred were captured. The Austrians lost 600 killed, wounded, and missing.

July 2, 1796 – The clashes at NEUWIED in 1796 are not to be confused with the Battle of Neuwied, a battle on April 18, 1797. Digby Smith has little information about this action, which took place near a village on the eastern bank of the Rhine River in central western Germany, about 18 kilometers northwest of Koblenz and the confluence of the Rhine and the Moselle. The Hessians lost 147 killed, wounded, and missing, mostly the latter.

August 17, 1796 – On page 120 is listed SULZBACH (link is to German lang. Wikipedia art. on battle. It provides details from French and German sources ). Digby Smith lists this battle as a ‘clash.’

At Sulzbach, a small village 45 km (28 mi) east of Nuremberg, Jean-Baptiste Kléber led a portion of the Army of the Sambre and Meuse against Lieutenant Field Marshal Paul von Kray. Of the Austrian force, 900 were killed and wounded, and 200 captured. The 20e DbdLé were distinguished with honors in a clash at SULZBACH, where they beat off a charge by the Austrian Calvary.

August 24, 1796 – BATTLE OF AMBERG (p 120) – The order of battle is listed as the same as Wurztberg, but, according to Digby Smith, exact details are missing. In addition to Le Var, Amberg is one of the battles inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe.

Charles struck the French right flank at this battle while Wartensleben attacked frontally. The weight of numbers overcame the French Army of the Sambre and Meuse and Jourdan retired northwest. The Austrians lost only 400 casualties of the 40,000 men they brought onto the field. French losses were 1,200 killed and wounded, plus 800 captured out of 34,000 engaged.

Although it was a loss, Amberg was inscribed among the victorious battles of the French Army.

September 3, 1796 – The Battle of WÜRZBURG was fought on September 3, 1796, and the 20th Demi-brigade Light Infantry is listed as under GdD Grenier’s command.

The battle was fought between an army of the Habsburg monarchy led by Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen, and an army of the First French Republic, including the 20e DbdLé led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. The French attacked the archduke’s forces, but they resisted until the arrival of reinforcements, which decided the engagement in favor of the Austrians. The French retreated west toward the Rhine River. Würzburg is 95 kilometers (59 mi) southeast of Frankfurt.

The Summer of 1796 saw the two French armies of Jourdan and Jean Victor Marie Moreau advance into southern Germany. They were opposed by Archduke Charles, who supervised two weaker Austrian armies commanded by Wilhelm von Wartensleben and Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour. At the Battle of Amberg on August 24, Charles concentrated superior numbers against Jourdan, forcing him to withdraw. At Würzburg, Jourdan attempted a counterattack to halt his retreat. After his defeat, Charles forced Jourdan’s army back to the Rhine. With his colleague in retreat, Moreau was isolated and compelled to abandon southern Germany.

Unfortunately for Moreau, Jourdan’s drubbing at Amberg, followed by a second defeat at Würzburg, ruined the French offensive; the French lost any chance of reuniting their front; both Moreau and Jourdan had to withdraw to the west.

September 16, 1796 – Listed on page 124 of Smith’s Data Book, this clash occurred at LIMBURG on 16–18 September. Charles defeated the Army of Sambre & Meuse in the Battle of Limburg. Kray assaulted Grenier’s troops on the French left wing at Giessen but was repulsed. In the struggle, Bonnaud was severely wounded and died six months later. Meanwhile, Charles made his main effort against André Poncet’s division of Marceau’s right wing at Limburg an der Lahn. After an all-day combat, Poncet’s lines still held except for a small bridgehead nearby Diez. Though not threatened, that night, Jean Castelbert de Castelverd, who was holding the bridgehead, panicked and withdrew his division without orders from Marceau-Desgraviers. With a gaping hole on their right, Marceau-Desgraviers and Bernadotte (now returned to his division) made a fighting withdrawal to Altenkirchen, allowing the left wing to escape. Marceau-Desgraviers was fatally wounded on the 19th and died the following day. This permanently severed the only possible link between Jourdan’s and Moreau’s armies, leaving Charles free to focus on the Army of the Rhine and Moselle.

The French armies retreated across the Rhine, thus ending the Rhine Campaign of 1796.

1797

Meanwhile, way down in Northern Italy…

A brash, young up-and-comer named Napoleon Bonaparte was winning victory after victory in the first Italian Campaign. Still, from the early Summer of 1796 until the Winter of ’97, he was plagued by the need to end the siege of Mantua (and the secret desire to run off to Egypt). So, he insisted that the Directory take 14 Demi brigades from the Rhineland and move them down into Northern Italy.

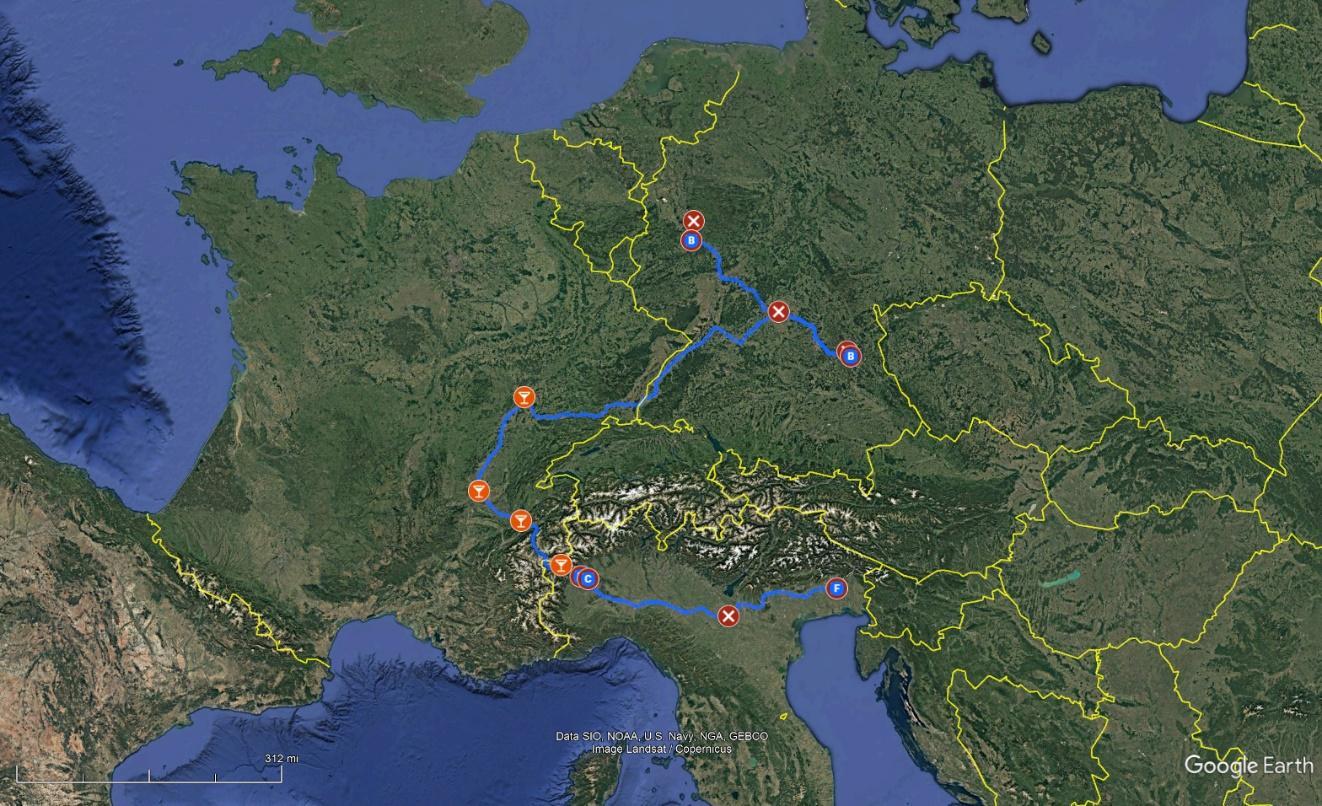

January 1797 – BERNADOTTE CROSSES THE ALPS – The French began transferring two divisions to Bonaparte’s army in Italy. Bernadotte’s 12,000 from the Army of Sambre and Meuse and Delmas’s 9,500 from the Army of Rhine and Moselle went south to support Bonaparte’s approach to Vienna.

General Bernadotte set out with 20,000 men, including the 20e DbdLé, divided into two divisions, and reached the Mont-Cenis massif via DIJON, LYON, and CHAMBÉRY; from there, he headed towards SUSA and then TURIN located in the Piedmontese territory. THIS GREAT MARCH ACROSS THE ALPS, ACCOMPLISHED IN THE MIDDLE OF WINTER AND DESPITE SNOWSTORMS, IS CONSIDERED A REMARKABLE FEAT FOR THE TIME.

But the real headline here is that my great-great-great-great-grandfather crossed the Swiss Alps three years and three months before Napoleon did!

14-15 January 1797 – The battle of RIVOLI was under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte, and the 20th Demi brigade is listed as being at that battle. The Battle of Rivoli, fought on January 14-15, 1797, was a decisive engagement during Napoleon Bonaparte’s Italian campaign in the War of the First Coalition. The battle occurred near the village of Rivoli Veronese in the Republic of Venice. Napoleon’s Army of Italy, numbering around 22,000 men, faced off against a more significant Austrian force of approximately 28,000 troops under the command of General Jozsef Alvinczi. Despite being outnumbered, Napoleon’s strategic insight and the effective use of terrain allowed the French to achieve a significant victory.

The Austrian army aimed to relieve the besieged fortress of Mantua, but the French thwarted their efforts. Napoleon’s forces held defensive positions on the Trambasore Heights, repelling multiple Austrian assaults. The French reinforcements, led by generals such as André Masséna and Barthélemy Joubert, played a crucial role in consolidating the French lines and counterattacking the Austrian columns. The battle demonstrated Napoleon’s tactical brilliance and ability to inspire his troops under challenging conditions.

The victory at Rivoli had far-reaching consequences. It marked the end of Austria’s attempts to break the French siege of Mantua, leading to the fortress’s surrender in February 1797. This triumph solidified French control over northern Italy and significantly weakened Austrian influence in the region. The Battle of Rivoli is often cited as a testament to Napoleon’s military genius and capacity to turn the tide of battle in his favor, even when faced with superior enemy numbers.

General Barthélemy Joubert played a significant role in the Battle of Rivoli, commanding a division of the French Army of Italy that included the 20e DbdLé. His forces were crucial in reinforcing the French positions and countering the Austrian attacks. Joubert’s division was initially stationed at the village of Rivoli, where they faced intense pressure from the Austrian columns.

Despite the challenging conditions, Joubert’s leadership and the resilience of his troops helped to hold the line against the Austrian assaults. His division’s steadfast defense allowed Napoleon to execute his strategic maneuvers, ultimately leading to the French victory. Joubert’s actions at Rivoli earned him recognition and further solidified his reputation as a capable and courageous commander.

Joubert’s contributions to the battle ensured the French maintained their defensive positions and could launch effective counterattacks. His ability to inspire his men and maintain discipline under fire was a testament to his leadership qualities. The success at Rivoli highlighted Joubert’s military prowess and contributed to the overall success of Napoleon’s Italian campaign.

January 16, 1797 – The Siege of MANTUA (1796/97) began August 27, 1796, several months before the 20th Demi brigade arrived in Italy; however, Lucien’s unit participated in the final days of the siege, and a part of that was a battle that occurred in January known as known as LA FAVORITA. The ancient fortress that was Mantua capitulated on February 2, 1797. The stats for La Favorita are as follows:

- French army (about 15,000 men) under General Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Austrian army (approximately 15,000 men) under Generals Dagobert Sigismund von Wurmser and Giovanni Provera.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 1,200 men killed or wounded, 1,800 prisoners.

- Austrian army: 1,300 men killed or injured, 4,700 prisoners, 22 cannons.

The Battle of La Favorita completed the success obtained at Rivoli by preventing the Austrian troops of General Wurmser from escaping from Mantua, where they had been blocked for four months. The fall of the city, a strategic lock of Northern Italy, was only a matter of days. The road to Vienna opened before Bonaparte.

March 16, 1797 – A final battle of the First Italian Campaign occurred at VALVASSONE on March 16, 1797. It is listed as a clash on page 133 of the Data Book.

From the French language Wikipedia: The Battle of Valvasone (March 16, 1797), also known as the BATTLE OF TAGLIAMENTO, saw a First French Republic army led by Napoleon Bonaparte attack a Habsburg Austrian army led by Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen. The Austrian army fought a rear guard action against the French vanguard led by Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte at the crossing of the Tagliamento River. Still, it was defeated and withdrew to the northeast. The French troops crossed the river at Valvasone, and the battle developed on the opposite bank, mainly between the little villages of Gradisca (now in the municipality of Sedegliano) and Goricizza (now in the city of Codroipo). A French division cut off and captured an Austrian column at Gradisca d’Isonzo (Capitulation of Gradisca) the following days. The actions occurred during the War of the First Coalition, part of the French Revolutionary Wars. Valvasone is located on the west bank of the Tagliamento 20 kilometers (12 mi) southwest of Udine, Italy. Gradisca d’Isonzo lies on the Isonzo River 14 kilometers (9 mi) southwest of Gorizia, Italy.

The War of the First Coalition ended in Oct 1797 with the Treaty of Campo Formio, ceding Belgium to France and recognizing French control of the Rhineland and much of Italy. The ancient Republic of Venice was partitioned between Austria and France. This ended the War of the First Coalition, although Great Britain and France remained at war.

1798

In the Summer of 1798, the 20e DbdLé showed up in an unexpected place, albeit only briefly. In June 1798, Bonaparte left northern Italy and headed south; his destination was EGYPT. Oddly enough, the 20th Demi Brigade Light Infantry appears in the list of units in the MALTESE EXPEDITIONARY FORCE headed for the island of MALTA (the ultimate and secret destination was Egypt.)

However, the 20e DbdLé does not appear in any lists regarding this effort that wound up in Egypt in 1798. The unit does not appear to have followed Napoleon to Egypt, nor did Napoleon leave it to garrison Malta (and ultimately surrender to the British. ) As Digby Smith has pointed out several times, the units listed on paper did not always reflect reality.

As I mentioned earlier, according to the French Wikipedia article regarding the 20e DbdLé during 1798, they were on duty in Switzerland. So we know they were NOT in Egypt and the Levant, but we do not know any details as those details are missing from Digby Smith’s Data Book.

The 20e DbdLé was not in Egypt; they must have been in Switzerland. So, perhaps earlier in the year 1798, this might have been their itinerary…

- March 5, 1798 – French troops enter BERN.

- April 12, 1798 – The Helvetic Republic, a French client republic, is proclaimed following the collapse of the Old Swiss Confederacy after the French invasion; Aarau becomes the republic’s temporary capital.

- April 26, 1798 – France annexes GENEVA.

- June 7, 1799 – Four days of fighting ends in victory for Archduke Charles and the Austrian army over the French army under André Masséna at the First Battle of Zurich

1799

For the year 1799, I do not know where the 20e DbdLe was before August. In Smith’s Data Book, the 20e is listed at the Battle of Novi under the command of GdB Serras in the Left Wing of the Army of Italy led by General Joubert.

August 15, 1799 – The BATTLE OF NOVI was a French loss. The Battle of Novi (August 15, 1799) saw a combined army of the Habsburg monarchy and Imperial Russians under Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov attack a Republican French army under General Barthélemy Catherine Joubert. As soon as Joubert fell during the battle, Jean Victor Marie Moreau immediately took command of the French forces. After a prolonged and bloody struggle, the Austro-Russians broke through the French defenses and drove their enemies into a disorderly retreat. In contrast, French division commanders Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon and Emmanuel Grouchy were captured. Novi Ligure is in the province of Piedmont in Northern Italy, 58 kilometers (36 mi) north of Genoa. The battle occurred during the War of the Second Coalition, which was part of the French Revolutionary Wars.

The French losses were 1500 killed, 5500 wounded, 4500 captured and missing, 37 guns, 40 ammunition wagons, and eight colors. General Joubert was dead, and four generals were captured.

October 24, 1799 – FIRST CLASH AT NOVI was a French victory, and it’s possible that the 20th Demi brigade was there under the command of General Suchet. It was also known as the SECOND BATTLE OF NOVI.

The Second Battle of Novi or Battle of Bosco (October 24, 1799) saw a Republican French corps under General of Division Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr face a division of Habsburg Austrian soldiers led by Feldmarschall-Leutnant Andreas Karaczay. The Austrians defended themselves stoutly for several hours, relying on their superior cavalry and artillery. By the end of the day, the French and allied Poles had routed the Austrians from their positions in this War of the Second Coalition action. Novi Ligure is south of Alessandria, Italy.

Napoleon left Egypt and returned to France. He returned in Oct 1799, and on 18 Brumaire An VIII (Samedi November 9, 1799), Napoleon staged a coup d’etat and made himself First Consul, thus replacing the Directory.

November 4, 1799 – The 20eDbdLé was maybe at the BATTLE OF GENOLA, as exact details are missing. The Battle of Genola or Fossano (November 4, 1799) was a meeting engagement between a Habsburg Austrian army commanded by Michael von Melas and a Republican French army under Jean Étienne Championnet. Melas directed his troops with more skill, and his army drove the French off the field, inflicting heavy losses. The War of the Second Coalition Action represented Italy’s last significant French effort in 1799. The municipality of Genola is located in the region of Piedmont in northwest Italy, 27 kilometers (17 mi) north of Cuneo and 58 kilometers (36 mi) south of Turin.

Championnat became the army commander after Barthélemy Catherine Joubert died in the French defeat at Novi in August. He aimed to keep the fortress of Cuneo under French control. Championnet and Melas advanced in November, and their armies collided in Genola. The French were forced to retreat into the Alps, leaving Cuneo to be besieged and captured on December 3, 1799. A typhus epidemic ravaged the poorly fed and clothed French army during the winter; the disease claimed the lives of Championnet and many others.

November 6, 1799 – The 20e DbdLé was at the SECOND CLASH AT NOVI, also known as the THIRD BATTLE OF NOVI. It was a French victory.

The Third Battle of Novi (November 6, 1799) saw a French Republican corps commanded by Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr defend itself against an attack by a Habsburg Austrian corps led by Paul Kray during the War of the Second Coalition. Saint-Cyr led the right wing of the French Army of Italy, which defended Genoa. Saint-Cyr advanced his troops into the lowlands but withdrew into the hills near Novi when Kray appeared with a superior force. Saint-Cyr did not have enough horses to move his artillery, so he tried to lure his Austrian opponents into attacking his four hidden guns. Finally, Kray advanced and fell into the trap; the French guns opened fire, and Saint-Cyr’s men counterattacked, inflicting severe losses. Wisely, Saint-Cyr did not follow his retreating foes into the plain where the Austrian artillery and cavalry waited.

November 13, 1799 – The 20e DbdLé was maybe at MONDOVI on November 13, 1799, where a skirmish occurred, resulting in an Austrian victory that is the end of the battle season in 1799

1800

The order of the battle for the army of Italy on April 5, 1800, shows the 20th Demi Brigade Light Infantry with 850 men under General of the division (GdD) SUCHET and GdD CLAUSEL.

12 April 1800 – Suchet was at SAN GIACOMO on 12 April 1800, clash

May 1, 1800 – The 1800 Battle of Loano is not to be confused with the BATTLE OF LOANO (23–24 November 1795), a French victory that made the name monument-worthy. However, the action at Loano on 1 May 1800 was a victory for Austrian forces over French forces. According to Clash of Steel Battle Database: “[It was] a contact between the Austrians pushing along the coast towards France and some of Suchet’s centre wing of the army of Italy. Suchet fell back with few casualties on either side.”

22-27 May 1800– VAR river occurred in May with SUCHET commanding the 20th Demi Brigade Light Infantry and three line infantry regiments with two squadrons of Calvary. The 20eDBdLe was distinguished in clashes with the Austrian calvary. Austrians broke off from the attempt to cross the Var River when they learned that Napoleon had crossed the Alps via the Great Saint Bernard pass and was headed for either MILAN or TURIN. All of this happened when the British laid siege to Genoa. The siege lasted from April 19 to four June 1800. Several thousand French soldiers died during the siege due to starvation and sickness.

May 1800 – Napoleon executed an even more daring plan than earlier, and that was to catch the Austrians by surprise. To do this, he took his troops – 40,000 men and field artillery – over the Alps and the Great St. Bernard Pass.

Many historians say that “no army attempted such a thing since the days of Hannibal.” Yet they forget that three years earlier, General Bernadotte (the future King of Sweden), along with two divisions of the French army (including the 20e DbdLé), crossed the Alps from CHAMBÉRY to SUSA in Italy in the dead of the winter of 1797.

June 9, 1800 – 20e DbdLé was NOT at the battle of MONTEBELLO

June 14, 1800 – 20e DbdLé was NOT at the battle of MARENGO, which marked the end of the Second Italian Campaign. On the morning of June 14, Napoleon faced the Austrians at MARENGO outside of Milan. By the end of the day, there were 6,000 French casualties, but nearly twice as many Austrians had been killed or wounded. The French had won.

End of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1803)

The Second Italian Campaign culminated in the Austrian Emperor suing for peace the following year. In 1802, France and Great Britain also signed a treaty of peace, and for the first time in almost ten years, Europe was at peace.

1802 Luc Francois left the army, having served his ten-year enlistment. It is probably a good thing that he did leave the army then because the hostilities between Great Britain and France recommenced on May 18, 1803, and the series of wars between France and the coalitions continued almost without a break until Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815.

After serving in Napoleon’s army, Luc Francois Gaume settled back in Montecheroux. In 1803, his occupation was listed as mason (maçon). In the birth record of his second child, Marie Julie, in 1809, his occupation was “tavern keeper” (cabarretier). From 1813 until he died in 1860, at age 86, his occupation is continually listed as couvreur, which is “roofer” or “tiler”.