I know of at least two ancestors who were veterans of the War of 1812. I’ve written an entire chapter about my mother’s great-great-grandfather, David Dobbs, who served as a third lieutenant in the Georgia militia during the Creek War of 1814. In this article, I want to share a discovery I made regarding my father’s great-great-grandfather, Corbett Pickering, and his service in the Pennsylvania militia during the War of 1812, and how I finally solved the mystery of a cryptic phrase I first encountered over a decade ago.

The War of 1812, often called America’s “second war of independence,” was a conflict between the United States and Great Britain that primarily arose from ongoing trade tensions and issues related to maritime rights. The British Royal Navy’s impressment of American sailors and the United Kingdom’s restrictions on U.S. trade while Britain was at war with France prompted calls for a declaration of war. The war also involved Native American allies of the British and American frontiersmen, which led to significant conflict in the western territories.

The war saw several key battles, including the burning of Washington D.C. and the Battle of New Orleans. The latter, famously led by Andrew Jackson, symbolized American resilience and determination. Although the war ended in a stalemate with the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, it ultimately established the United States as a force to be reckoned with on the world stage and had significant long-term effects on the nation’s future.

Until yesterday, all I knew of Corbett Pickering’s service in the War of 1812 was from a single line in a history of Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, published in the 1880s. On page 767 of the book, Ramanthus Stoker wrote: “[Corbett] served in the War of 1812 and went as far as Danville.”

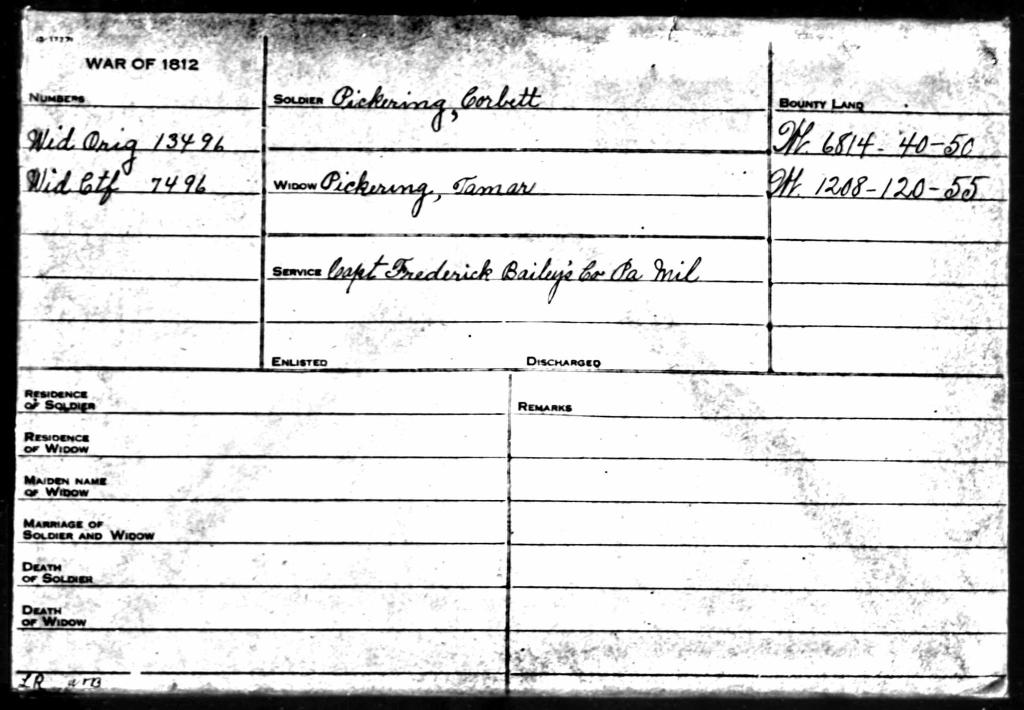

I googled “Danville in the War of 1812,” and it came up dry. That was over a decade ago, and until I made a related discovery yesterday, I do not think I tried searching again in the interim. Yesterday’s find was at Fold3.com. It was a card image from the “U.S., War of 1812 Pension Application Files Index, 1812-1815”

The only useful information on the card was “Captain Frederick Bailey’s company Pennsylvania militia.” This was later used for confirmation.

In the meantime, I thought I might search for “He went as far as Danville,” thinking that phrase might be a euphemism for something. Much to my chagrin, I got multiple hits on “Danville” in the text of the same book by Ramethus Stocker, including a second appearance of the exact phrase.

Here’s what happened: In August 1814, 2,500 soldiers under General Ross had just arrived in Bermuda aboard HMS Royal Oak, three frigates, three sloops, and ten other vessels. Released from the Peninsular War by victory, the British intended to use them for diversionary raids along the coasts of Maryland and Virginia. The Brits decided to employ this force, together with the naval and military units already on the station, to strike at the national capital. Anticipating the attack, valuable documents, including the original Constitution, were removed to Leesburg, Virginia. The British task force advanced up the Chesapeake, routing Commodore Barney’s flotilla of gunboats, carried out the Raid on Alexandria, landed ground forces that bested the US defenders at the Battle of Bladensburg, and carried out the Burning of Washington.

United States Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr. insisted that the British would attack Baltimore rather than Washington, even as the British army and naval units were on their way to Washington. Brigadier General William H. Winder, who had burned several bridges in the area, assumed the British would attack Annapolis. He was reluctant to engage because he mistakenly thought the British army was twice its size.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania began mobilizing its militia, which was ultimately federalized but apparently never put to use. In Corbett’s case and possibly his father–in–law, John Denny, the men from Gibson were marched for a week south to Danville, a transportation hub on the northern branch of the Susquehanna River. After doing what armies have done throughout history—“hurry up and wait”—the men were discharged and marched back home.

Here’s what I found in Stocker’s book:

Page 212

“The War of 1812 furnished practical reasons for military duty. An ‘Appeal to Patriots,’ published in the Luzerne County papers in 1813, offered a bounty of $16 (for enlistment for three years) and three months’ pay at $8 per month, with one hundred and sixty acres of land. Those who enlisted for only eighteen months received no laud.

“Complaint of taxes increased as hostilities continued. May, 1814, bounty was raised to $124, besides 160 acres. In the summer a call appeared in the Luzerne County papers (none were then established in Susquehanna County) for a meeting immediately after court, 23d August, at Edward Fuller’s, ‘ friendly to a restoration of peace or a more vigorous prosecution of the war.’

“The burning of the Capitol at Washington stimulated militia organizations. At a militia election, in the summer of 1814, Frederick Bailey was elected colonel.”

“Isaac Post was appointed inspector of 2d Brigade. From his diary we learn that, October 23, 1814, he received orders for marching the militia, and set out for Wilkes-Barre on the 24th. Arrived at Danville, Pa., November 1 ; with detachment of militia on the 13th; received orders to halt on the 19th; to dismiss the detachment 21st; the whole was discharged on 24th and 25th, same month.’ Colonel F. Bailey accompanied this expedition.

“It was held up to ridicule, while the militia were waiting for their pay until April, 1819, and afterwards for its fruitlessness. Ezra Sturdevant, drafted from Harford or New Milford, was left sick at Danville, died, and was buried with military honors. It is laughingly asserted that Major Post brought back one hand-rifle and one tin camp-kettle as the spoils of this expedition.”

Page 329

“[Walter Lathrop] was active as an officer and took troops as far as Danville, Pa., during the War of 1812— 14, where they were dismissed, owing to the proclamation of peace.”

Page 514

“…the famous Danville expedition starting and returning within the same month.”

Regarding bounties and pensions, the federal government offered bounty land warrants to encourage enlistment and reward service during the war. The warrants were based on acts passed in 1811 and 1812, and surviving veterans could apply under acts passed in 1842, 1850, 1852, and 1855. Most veterans received 160 acres of land.

Congress provided modest pensions for men who were disabled in service, following British practice. In 1818, a pension law allowed compensation for service regardless of disability, but it was later amended to include soldiers who could not earn a living. The Pension Act of 1832 allowed pensions based on service again and made it possible for a veteran’s widow to receive pension benefits. Starting in 1871, veterans of state militias who were federalized received pensions for their War of 1812 service, and their widows received pensions in 1878. Under the terms of the law, a widow would receive half of her husband’s pay for seven years after his death.

For details of my mother’s Southern ancestor’s service during the war, see On Down the Tallapoosa to the Gulf of Mexico.