After 40+ years of research on my Irish ancestors, I have learned that some were Native Irish, some were Anglo-Irish, some were Ulster Scots, and some may even be Vikings (or Norsemen). Some of them were Roman Catholic, some were Church of Ireland, some were Presbyterians, and some, in the distant past, were Celtic pagans. Some were Loyalists, some were Rebels, some were Scotch Covenanters, some were Williamites, some were Jacobites, some were Cromwellian Roundheads, and some were Fenians. My father had a friend whose older brothers had participated in the Easter Uprising of 1916, and my grandmother would joke about someday winning the Irish Sweepstakes. My face may not be a map of Ireland, but I cannot deny that I’ve got it in me.

Most of my Irish ancestors came over around the time of the famine in the 1840s. Some migrated to the British American colonies in the previous century. Over the years, I have learned a lot, but there is still much to learn.

A few years ago, I undertook an autosomal DNA test at Ancestry.com. The ethnicity estimate that came with the results was quite surprising – it revealed a stronger Irish lineage than I had expected. What caught me off guard even more was the significant Scottish ancestry that the estimate uncovered. This estimate has been revised twice since I initially reviewed it, and it currently suggests that I am 40% Scottish and 34% Irish. The remaining percentage is a mix of my Flemish, German, Welsh, and Viking ancestry.

This revelation was initially unexpected, but after educating myself on the inheritance of DNA from parents to children, and considering the number of my great-grandparents who hailed from Ireland, everything started to fall into place. Ancestry breaks down the overall estimate and provides percentages of each ethnicity I inherited from my parents.

It shows my father contributed all my 34% Irishness and 6% Scotch-ness, while my mother contributed 34% of my Scottish ethnicity.

At first, the estimate seemed to skew a little too much towards Scotland until I realized that two of my great-great-grandparents came from Ulster (Northern Ireland), which is included in the Scottish sphere of influence, and at least one branch originated in Scotland.

Paternal Grandmother

On my father’s side the Irish estimate gets very specific and connects me to the ethnicity region in Western Ireland known as Connacht, which along with Ulster was one of the four ancient provinces of the Emerald Isle.

This is obviously where my paternal grandmother’s family came from. Her name was Geraldine O’Malley – indeed, a very Irish name. Geraldine’s parents, Patrick O’Malley and Molly Hooks, were both born in North America – he was born in Canada, and she was born in New York. Both their parents were born in Ireland. It was after I did my DNA that I learned that Geraldine’s grandparents, Martin O’Malley and Anna Kirby, were married in 1841 at St Patrick’s church in the little village of Islandeady in County Mayo in Connacht – the ancient seat of the Ó Máille family and the home of the legendary pirate queen Grace “Granuaile” O’Malley. Alas, this is all I know of my O’Malley & Hooks families, and I hope someday to trace the family further.

Paternal Grandfather

I am certain that there are no Irish on my father’s father’s side of the family as they were predominately Franco-Belgian. Yet, it is unknown where the 6% Scottish on my father’s side came from. It could be that my paternal grandmother’s “native” Irish ancestors had Scottish ancestors (heaven forbid!) or it may be from the Pickering ancestors of my great-grandmother, Della Pickering Gaume. Her mother’s family supposedly originated from the Northumberland region of England back in the 17th century.

Maternal Grandfather

The amount of Irishness I have uncovered on my mother’s side of the family gets increasingly complex as I go along. Starting with with my maternal grandfather, James Monroe Dobbs, we know that some of his ancestors came from Wales (the ethnicity estimate shows I am 3% Welsh on my mother’s side). His father’s ancestors arrived in America in the 18th century or earlier and the Dobbs may have come by way of Ireland. Some family researchers connect my Dobbs family to the family of Arthur Dobbs, the colonial Govenor of North Carolina and further to a castle near Carrickfegus in Ulster that was built in 1730.

We do know that Monroe’s great-grandmother, Elizabeth McMullan, was the granddaughter of John McMullan, an upcountry Georgia planter and Revolutionary War veteran who, according to a family legend, was born and raised in Dublin to a family of sailmakers.

Maternal Grandmother

My great-grandmother, Katherine “Beanie” Bannon was born in Louisville, Ohio to parents who were both born in the Ulster province of Northeastern Ireland.

Bannon Family

Her father’s name was Richard Bannon. The origin of the Bannon surname is Irish and Manx. It is an Anglicized form of the Gaelic Ó Banáin, which means ‘descendant of Banán’. Banán is a personal name that is a diminutive of bán, meaning ‘white’, ‘fair’, or ‘pale’. The Bannon family name was first found in the barony of Clonisk, in the southern tip of County Offaly, where a medieval sept of this name was found.

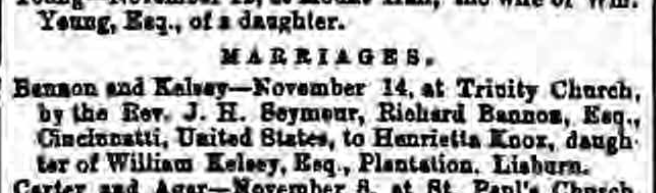

My great-great-grandfather, Richard Bannon, was born about 1818 in Downpatrick, County Down. He and his brother Patrick came over in 1843, and the rest of his family followed in 1849 in the depths of the famine crisis in which a million Irish perished. A dozen years later, during the American Civil War, Richard left America and returned to Ireland. The story was that he returned at the age of 40-something and went back to Belfast wanting to marry “a nice Irish girl.” While there, he was introduced to Henrietta Knox Kelsey, his cousin’s sister-in-law. The courtship was brief, and the couple were married in November 1865 in a Presbyterian Church in Belfast, Northern Ireland. That church, Trinity Church, was destroyed by German Luftwaffe bombers during the Belfast Blitz in 1941.

After returning to the US, Richard & Henrietta were married in a Roman Catholic ceremony officiated by Richard’s good friend, the Bishop of Coventry, Kentucky.

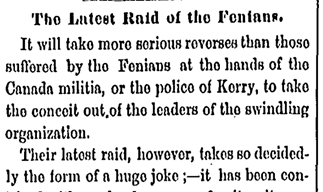

This is speculation on my part, but Richard’s return to Ireland may have been a secret mission of the Fenian Brotherhood. We know that his younger brother, Patrick, was in a leadership role as one of half a dozen “Senators” who answered only to the organization’s president, who lived in a lavish mansion in New York City. Each Senator was headquartered in a US city with a sizable population of Irish immigrants – Louisville, Kentucky, a river boomtown, being one of them. During the American Civil War, the Fenians raised a large sum of money, mainly from small-dollar donors such as liverymen, bricklayers, maids, and washerwomen. After the Civil War, the Fenian Brotherhood attempted to invade Canada, not once but numerous times, to overthrow the British government.

The Fenian Brotherhood was an Irish republican organization founded in the United States in 1858 by John O’Mahony and Michael Doheny. It was a precursor to Clan na Gael and a sister organization to the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). The Fenians were secret political organizations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries dedicated to establishing an independent Irish Republic. The Fenian Brotherhood operated freely and openly in the United States, while the IRB was a secret, outlawed organization in the British Empire.

The Fenian Brotherhood attempted to invade Canada multiple times between 1866 and 1871, in what are known as the Fenian Raids. These incursions were carried out on military fortifications, customs posts, and other targets in Canada, which was then part of British North America. The Fenians hoped to seize Canadian territory and use it as a bargaining chip to pressure Britain into granting Ireland independence. However, all these raids ended in failure.

Neither of the Bannon brothers were implicated as being involved in the Fenian raids. In fact, The U.S. government did little to prevent these raids, possibly due to resentment over British support for the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Despite their lack of success, the Fenian Raids were a significant factor leading to Canadian Confederation, as the provinces united to face the threat of invasions.

Kelsey Family

Henrietta’s father was William Kelsey. He owned a linen factory known as Plantation Mills. The family lived on an estate called “Plantation.” The Kelsey family home is still standing near Lisburn in Hillsbourough (County Antrim) outside of Belfast.

The origin of the Kelsey surname of Northern Ireland is not clear, but it may be related to the English surname Kelsey, which comes from an Old English place name in Lincolnshire, meaning “Ceol’s island” or “island of the ships”. Alternatively, it may be a variant of the Irish surname Kelly, which derives from the Gaelic Ó Ceallaigh, meaning “descendant of Ceallach”. Ceallach is a personal name that may mean “bright-headed” or “strife”.

I know very little about Henrietta’s father, William Kelsey. He was born about 1800 in Northern Ireland. He died February 7, 1869, at the family estate.

Knox Family

On the other hand, a significant amount is known about the family of Henrietta’s mother, Mary Emily Knox. Henrietta’s father, William Kelsey, climbed a few rungs of the social ladder when he married Mary Emily. She was of the Knox family of Scotland on her father’s side, and on her mother’s side, Mary could trace through several generations of Anglo-Irish prelates and noblemen.

A couple of years ago, I wrote a post titled “My Mother’s Mother’s Mother…” in which I wrote of finding my mother’s (9X) mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s mother – a woman named Mary Jenkinson who lived in 17th century England. In that same article, I wrote of discovering an ancestor named Rev. John Winder (1658-1733), who was Prebendary of Kilroot and close friends with the 18th-century satirist Jonathan Swift. These were the ancestors of Mary Emily’s mother, Sophia Anne Rogers. Her lineage was primarily Anglo-Irish. Sophia’s family were members of the so-called “Protestant Ascendancy” who came to Ireland from England during the Williamite War in the late seventeenth century.

This means the Scottish connection is primarily through Mary Emily’s father, John Knox, Esq. of Maze House, Dromore, Co. Down. He was born about 1768, and in his early twenties, he was an officer in command of a troop of Light Dragoons and a Battalion of Light Infantry of the Lower Iveagh Legion. Lower Iveagh is the name of a barony in County Down. Under what circumstances John oversaw these units and whether they saw action in one of Britain’s many battles of the day are unknown.

Thanks to Google Books, I found in a catalog of military memorabilia from the 19th century a description of a medal presented by John Knox, Esquire of Dromore, to one of the soldiers under his command. The inscription read “Obtained by John Burn from John Knox, Esq. of Dromore for his superior merit in the corps,” along with the date “August 19, 1789.” The record shows that John and Sophia married when he was aged twenty-nine. This would be consistent with a ten-year stint in the military.

One book I have seen quoted more times than others is titled Genealogical Memoirs of John Knox and of the Family Knox by The Reverend Charles Rogers, LLD., Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. The family of Mary Emily, beginning with her great-grandfather, starts on page 51 of Rogers: “At Dromore, in the county of Down, John Knox of the family of Ranfurely purchased a portion of land early in the 17th century. His son, Alexander, who owned the lands of Eden Hill near Dromore, left two sons, John and George. George, the second son, went to Jamaica about the year 1798…”

I need to interject here and highlight that even if George was in his forties in 1798, it appears implausible that his grandfather would have flourished in the early 1600s. This suggests that one or more generations are missing from Rogers’s narrative or that the immigrant John Knox arrived later – say, early in the 18th century.

Continuing page 51: …John, the elder son of Alexander Knox of Eden Hill, inherited the family estate and had (with several daughters) two sons, Alexander and George. Alexander, the elder son, entered the medical profession and became a surgeon in the Royal Navy; he afterward held a government appointment in Ireland.

Mary Emily Knox was among the several daughters of John Knox mentioned above. This fact is supported by obituaries, estate records, and DNA that connects Mary Emily to two siblings, Alexander and George, all children of John Knox of Dromore, Co. Down.

It seems that I have followed the family of Mary Emily Knox up to the shore of the Irish Sea and canna go further. The Knox family most definitely came from Scotland and most definitely came from the family Ranfurly; however, who and when continues to escape me.

John Knox, Esq of Dromore married Sophia Anne Rogers, daughter of Rev. George Rogers in 1797.

Rogers Family

For this line, I have traced back as far as Mary Emily’s great-grandfather, the Rev. George Augustus Rogers (1695-1769) – this would be my sixth great-grandfather. George Augustus Rogers was born on December 27, 1695, in Lisburn, Antrim, Northern Ireland. He married Ann Hanna on December 9, 1725, in Glenavy, Antrim, Northern Ireland. He died on July 24, 1769, in Clough, Kilkenny, Ireland, at 73. He was a Curate at several parishes in Northern Ireland in the mid-1700s, including Glenavy near Antrim, and he was the Rector of Donaghy from 1763 to 1769.

According to “Ireland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1620-1911”, Ann Rogers, daughter of George Rogers, was born May 30, 1773, First Presbyterian Church Belfast, Antrim, Ireland.

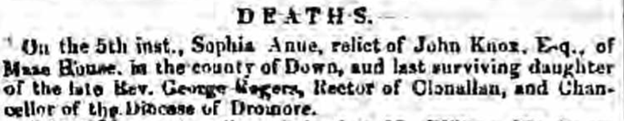

Sophia Anne Rogers’ death notice which appears in the Belfast Newsletter (July 6, 1849) states that Sophia Anne Rogers was the daughter of a Rev. George Rogers: “On the 5th inst., Sophia Anne, relict of John Knox, Esq. of Maze House, in the County of Down, and last surviving daughter of the late Rev. George Rogers, rector of Clonallen and Chancellor of the diocese of Dromore.“

According to several family trees, Maria (Mary) Benson was the wife of Rev. George Rogers and the mother of Sophia Anne Rogers.

Benson Family

Rev. Trevor Benson, Archdeacon of Down, was the father of Mary Benson and a great grandfather of Mary Emily Knox. Her great-grandmother was Jane Hutchinson. According to one researcher: “[Trevor’s] first wife, Jane, was a daughter of Samuel Hutchinson and sister of the Rt Rev Samuel Hutchinson, Bishop of Killala. She bore him two sons, Samuel and Hill, and three daughters.” Presumably, Maria (or Mary) was one of those three daughters.

Trevor Benson has a Wikipedia article in his name. The article consists of two lines:

Trevor Benson (1710-1782) was an Anglican priest in Ireland during the 18th Century.

Benson was born in County Down and educated at Trinity College, Dublin. He was Prebendary of Kilroot in Lisburn Cathedral from 1763 to 1768; and Archdeacon of Down from 1768 until his death.

Trevor’s father was the Rev. Edward Benson (1680-1741), Rector of Downpatrick, and Prebend of Down. Edward is my 7th great-grandfather.

Hutchinson Family

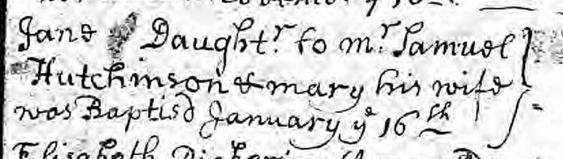

Jane Hutchinson was the wife of Trevor Benson and mother of Maria Benson. We have Jane’s baptism record. The record, in the year 1709, places her christening at Carsington, Derbyshire, England. It states:

“Jane, daughter of Mr. Samuel Hutchinson and Mary his wife was baptized January 16.“

According to a fellow researcher, Samuel Hutchinson was an Ensign in Lord Forbes’ Regiment at the Battle of Boyne 1 July 1690 (OS). This battle was a clash between the armies of James II, former King of England, and William III of Orange, who had recently deposed James and, with his wife, Mary, was the new ruler of Great Britain. The Battle, which occurred near the River Boyne about 30 miles from Dublin, Ireland, saw the Roman Catholic forces of James, which included troops from Ireland and France, face Protestant forces led by William, and included soldiers from the Netherlands, Europe, England, Ireland, and Scotland. The “Williamites” outnumbered the “Jacobites” 36,000 to 23,000 and won the Battle. The outcome of the Battle is considered the victory of the Glorious Revolution in England and also resulted in the Treaty of Limerick, which, for a time, ended the Civil War in Ireland.

Ironically, Forbes’ Regiment had been created in 1684 by James II under the command of Arthur Forbes, Earl of Granard, and passed to his son in1686. The Regiment was shifted between England and Ireland, and because it was made up of both Catholic and Protestant troops, it saw two purges in which one group or other was removed. In 1689 the Regiment was back in Ireland and when the Battle of Boyne occurred, it now supported William of Orange.

Winder Family

Another ancestor was also present at the Battle of the Boyne. This was my 8th great-grandfather, Rev. John Winder (1658-1733).

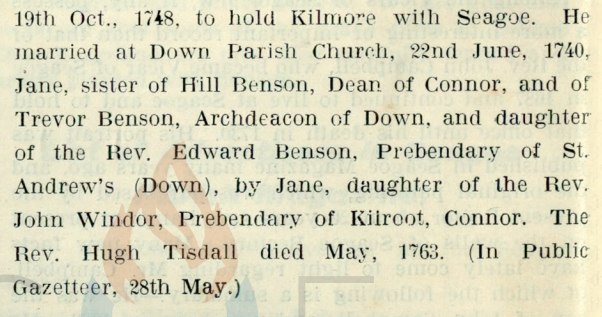

Sometimes information comes from strange places. Take, for example, the following found in a church news bulletin from 1927. The publication presents the life story of a man who was the church’s rector 200 years earlier. The man’s name was Hugh Tinsdale, and the bulletin states that he married a sister of Trevor Benson, Archdeacon of Down and that their father was the Rev. Edward Benson, Prebendary of St. Andrews (Down). Their mother was Jane, daughter of the Rev. John Winder, Prebendary of Kilroot & Connor. The dictionary defines a prebendary as a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in administering a cathedral or collegiate church. An archdeacon is a senior priest who is in charge of other priests.

John Winder (1658–1733) was a man of minor notoriety who lived in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. I have found him mentioned in several documents, including an excerpt from a book titled the Clergy of Clogher where it states that he was son of Col. Cuthbert Winder of Wingfield, Berkshire, and came to Ireland as chaplain to William III. The only area regarding John Winder where there is a lack of agreement is that some sources list his father as Peter Winder, an Army Cornet from Devonshire. He was the vicar of a few parishes in Northern Ireland, including Carmoney, and he succeeded the noted Anglo-Irish satirist Jonathan Swift as prebendary of Kilroot. Some correspondence between him and Swift have been preserved.

Another source provides further insight into Rev. Winders’ relationship with Jonathan Swift. The Ulster Journal of Archaeology – vol. 9 (1861), quotes one letter from Swift to Winder in which Swift gives instructions to Winder on some books that he left behind in Kilroot when he went to Dublin.

In the letter Swift writes:

The [book titled] Sceptis Scientifica is not mine, but old Mr. Dobbs, and I wish it were restored. He has Temple’s Miscellanea instead of it. If Sceptis Scientifica comes to me, I’ll burn it for a fustian piece of abominable curious virtuoso stuff. I hope this will come to your hand before you have sent your cargo, that you may keep those books I mentioned, and I desire you will write my name, and Ex dono [donated] before them in large letters.

The information I found on page six of that book initially excited me but upon closer examination I found a significant number of errors. Here is a transcription of page six with my observations/comments formatted as italicized boid and names of ancestors in bold red.

The Rev John Winder came to Ireland as a chaplain to King William III (at the Battle of the Boyne). He was married soon after his arrival to Jane Done or Doane daughter of Major Done of Cromwell’s army and Letitia Lyndon daughter of Roger Lyndon Esq of Carrickfergus

(see note below).

Jane Doane whose daughter Elizabeth Winder became the mother of George Macartney was a lineal descendant of Sir Cahir O Dogherty and his wife Rose O Neill the third daughter of Hugh O Neill the last and great Earl of Tyrone. (Note that I did not mark Sir Cahir as an ancestor because according to other sources, Cahir O’Doherty is listed as ‘d.s.p.’ This means that he ‘died sine prole’ that is without issue. Yet as seen below, according to this book he had three daughters one of which is my ancestor, Rosa O’Neill.)

Sir Cahir left three daughters

(1) the eldest

of whom married Sir William Brownlow of Lurgan

(2) the second became the wife of Colonel Cormac O’Neill of Broughshane (According to Burke’s Cormac married Mary daughter of Col. Thady O’Hara and died without issue in 1707.)

(3) and the youngest Rose married Captain Roger Lyndon of Carrickfergus whose son Roger married Jane Martin the daughter of John Martin by Letitia Caulfield, sister to the first Lord Charlemont.

Roger Lyndon‘s daughter Letitia was as already stated mother of Jane Doane who was married to the Rev John Winder and whose daughter Elizabeth became the mother of Lord Macartney. He was thus maternally descended from the two great Irish chieftains Hugh O’Neill and Sir Cahir O’Dogherty (The first man listed is correct and the second one is not. What I learned was that Rose O’Neill, daughter of Hugh O’Neill was married to Sean Og O’Doherty, the brother of Cahir. Their daughter Rosa O’Doherty was married to Roger Lyndon, the mayor of Carrickfergus.)

A note at the bottom of page 6 of the book reads:

Roger Lyndon was Mayor of Carrickfergus in 1643 He neglected or perhaps refused to burn a copy of the Scottish Solemn League and Covenant as ordered by the Government and for this omission was brought to the bar of the House of Lords where on his knees he was obliged to enter into security that he would faithfully superintend the burning of the obnoxious covenant.

The “Scottish Solemn League and Covenant” was an agreement established in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. This pact was between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians. The Scots agreed to support the English Parliamentarians in their disputes with the royalists, and both countries pledged to work for a civil and religious union of England, Scotland, and Ireland under a Presbyterian–parliamentary system. Based on his alleged conduct, Roger Lyndon was a Scotch Irish Presbyterian who opposed the government of King Charles I.

O’Doherty

The Rose O’Doherty family was also seen as troublemakers in the eyes of the English. The O’Doherty family, also known as Ó Dochartaigh, is an Irish clan that originated from County Donegal. They were a prominent sept of the Northern Uí Néill’s Cenél Conaill, and one of the most powerful clans of Tír Connaill. The O’Dohertys were originally chiefs of Cenél Eanna and later became rulers of Inishowen, a large peninsula in what is now County Donegal. The family name is one of the most ancient in Europe, tracing its pedigree through history, pre-history, and mythology to the second millennium BC.

The O’Dohertys are named after Dochartach, a member of the Cenél Conaill dynasty, which traced its lineage to Niall of the Nine Hostages. The clan motto is “Ár nDuthchas”, which translates to “Our Heritage”. Today, there are over 250 variations in the spelling of the name Ó Dochartaigh. The O’Dohertys’ rule over Inishowen ended in the early 17th century when their lands and possessions were confiscated following Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s rebellion.

Rosa O’Doherty pedigree can seen here in “A genealogical and heraldic dictionary of the landed gentry of Great Britain and Ireland” By John & Bernard Burke.

O’Neill

Hugh O’Neill, father of Rose O’Neill, also known as Aodh Mór Ó Néill or Hugh the Great O’Neill, was a prominent Irish Gaelic lord and the Earl of Tyrone. Born around 1550, he is best known for leading a coalition of Irish clans during the Nine Years’ War, posing the strongest threat to the House of Tudor in Ireland since the uprising of Silken Thomas against King Henry VIII. Despite his initial cooperation with the English crown, his dominance in Ulster led to deteriorating relations, culminating in skirmishes between his forces and the English in 1595. His victory at the Battle of the Yellow Ford on the River Blackwater in Ulster marked a significant defeat for the English, sparking a general revolt throughout Ireland.

The Flight of the Earls took place in September 1607, marking a watershed event in Irish history and symbolizing the end of the old Gaelic order. This event involved Hugh O’Neill, the 2nd Earl of Tyrone, Rory O’Donnell, the 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, and about ninety followers leaving Ulster in Ireland for mainland Europe. The departure was precipitated by the deteriorating relationship between the earls and the English crown, with the earls hoping to argue their case in London. However, when Rory O’Donnell decided to leave for abroad, O’Neill realized that staying would implicate him in a potential uprising, leading to his decision to join the flight. Their permanent exile marked the beginning of many departures from Ireland by native Irish over the following centuries.

Hugh O’Neill’s bones are interned beneath a church in Rome, Italy.

The inscription reads: “D.O.M. Hugonis principis ONelli ossa”

The inscription translates as follows:

D.O.M. = Deo Optimo Maximus = God is Great

Hugonis principis ONelli = Prince Hugh O’Neill

OSSA = abbreviation for bones. Meaning that remains were move to ossuary after being moved from a graveyard,

The inscription on the tomb subtly indicates that his followers considered him to be rightful heir to the throne of Ireland (and I guess you know what that makes me, right?)

HAPPY ST PATRICK’S DAY!