In a previous post, I recounted the discovery of one of my father’s ancestors known in legend as La Bete Canteraine, the beast of Canteriane – a werewolf. However, as I later found out, Hugues III de Campavaine was not the sole member of his family renowned for an active afterlife.

Turning my attention to a list of ancestors I had identified as participants in the military campaigns of the 11th and 12th centuries known as the Crusades, I found a total of six individuals. Among them were three who participated in the First Crusade (1096-1099) and another trio who joined the Third Crusade (1189-1192). Intrigued, I sought to uncover additional information about these men within the primary sources concerning the Crusades. To achieve this, I aimed to examine works such as Anna Komene’s Alexiad, the anonymously authored Gesta Francorum, and Raymond of Aguilers’ Historia Francorum – all of which are readily accessible on the internet.

Initially, it became evident that only two ancestors were part of the First Crusade. Concerning Robert III de Bethune, I realized that I had misconstrued a passage from the translation I obtained for Google Translate. The accurate interpretation indicated that Robert did NOT accompany Robert, Count of Flanders, to Palestine during the First Crusade. Instead, he remained behind with Countess Clementia of Burgundy, who served as the Regent of Flanders, offering her counsel and protection. At the onset of the First Crusade in 1096, Robert, aged fifty-six, likely assumed the role of a paternal figure for the young countess.

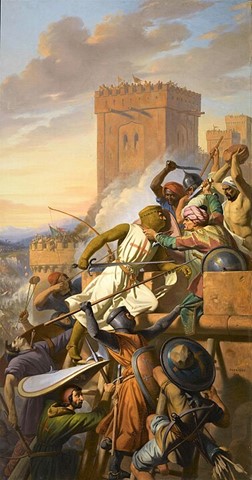

The two individuals who did participate in the First Crusade were Hugues II de Campavaine (1045-1130) and Hugues II d’Oisy et Crèvecœur (1075-1139). My expectations regarding Hugues d’Oisy were high due to the information presented in a Wikipedia article outlining his activities during the First Crusade. According to the article, Hugues took part in the siege of Nicaea, the battle of Dorylaeum, and the siege of Antioch. It further mentioned his ascent over Jerusalem’s walls during the Jerusalem siege and his presence at the Battle of Ascalon. Yet, my search through various books failed to yield further mention of d’Oisy’s exploits.

The same could not be said for Hugues II de Campavaine (1045-1130) and his son Enguerrand, an elder sibling of Hugues III. These two figures were repeatedly referenced in relation to the Siege of Antioch (1097-1098) and the Siege of Ma’arra (1098). They are subjects within the Chanson de Geste of Antioch (Chanson d’Antioche).

As indicated by Charles d’ Héricault author of La France guerrière récits historiques d’après les chroniques et les mémoires de chaque siècle (1868), Enguerrand, the adolescent son of Hugues II, displayed acts of heroism during the Antioch siege. On pages 97-98, the Chanson d’Antioche recounts how Enguerrand, the son of the Count of Saint Paul, made a significant discovery that enabled his comrades to seize control of a fortified bridge across the Oronte river.

Subsequently, Enguerrand (also known as Engleran or Angelram) met his demise during the Ma’arra siege. While one source suggests that his death resulted from an illness, Crusade chronicler Raymond d’Agiles asserts that Enguerrand fell in battle.

According to Histoire des Croisades Volume I (1812) by Joseph-François Michaud, the brother of Hugues III, aka La Bete Canteraine, made a post-mortem appearance:

“One day, as recounted by Raymond d’Agiles, Anselme [de Ribemont, the Count of Bouchain] witnessed the entrance of Angelram, the young son of the Count of St Paul, into his tent. Angelram had seemingly perished in battle at the siege of Maarah, yet he stood there alive. Anselme inquired, “How are you now so full of life, when I saw you dead on the battlefield?” Angelram responded, asserting, “Those who fight for Jesus Christ do not truly die.” Anselme queried the source of the radiant aura surrounding Angelram, to which the latter indicated a crystalline and diamond-studded palace in the sky. He revealed, “This beauty comes from there; it’s my abode. We are preparing an even grander one for you, where you shall reside soon. Farewell, until we meet again tomorrow.” With these words, as recorded by the historian, Angelram returned to heaven. Struck by this apparition, Anselme gathered several ecclesiastics and, the following morning, received the sacraments. Despite being in good health, he bade his friends a final farewell, explaining his imminent departure from the world in which they had shared time. Anselme was then struck in the forehead by a stone, which, according to historians, carried him to the magnificent palace awaiting him. This remarkable account, lending credence among the Crusaders, is but one of many such stories that history has compiled. It is worth noting that extreme destitution consistently rendered the Crusaders more superstitious and credulous.” [pg 348]